In this post, we present significant breaks in the linear dependence between the CPI and dGDP (i.e. between two measured time series) in Germany as related to new definitions of inflation. The case of Germany, however, has a very specific meaning – this country is the economic leader of the European Union. In the Annex below, we present an independent opinion on the behavior of economic leaders, including Germany, formulated 105 years ago.

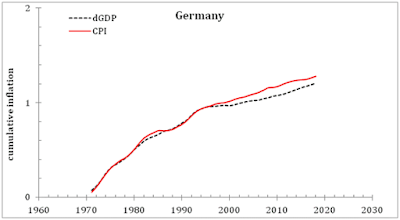

Figure 1 presents 4

panels illustrating the process of the definitional break findings as applied

to Germany. Panel a) depicts two inflation curves – for CPI and GDP deflator.

One can see that the CPI curve is slightly above the dGDP curve from the mid-1990s.

Panel b) presents similar curves, but for cumulative inflation as the running

sum of inflation readings. The slightly higher CPI inflation is now producing a significant deviation of the cumulative curves. Pane c) shows the difference

between the curves and panel a) and panel b). The difference between the two

cumulative curves reveals a break followed by deviation as a linear function of

time. Using the slope of the difference, one can calculate the coefficient of the linear

correction (1.5) needed to fit the CPI and dGDP curves. Panel d) shows the

original CPI curve and the corrected dGDP curve, i.e. the dGDP curve multiplied

by a factor of 1.5 since 1997. There is still some deviation between the curves

after 2013. It might be a manifestation of a new break. We are going to follow

the new deviation and will report on it in the future. The presence of

definitional breaks is similar to those observed in different countries.

However, timing and circumstances related to the ECB creation win the

headquarters in Frankfurt make the case of Germany suspicious. We wrote about

the potential benefits of German leadership in previous posts. Here, we are

going to support the case.

Figure 2 depicts curves

of the real GDP per capita growth in several European countries between 1960

and 1996. In order to provide a consistent

view of the total growth, we normalize all curves to their respective (GDPpc) levels

in 1960. Two champions are Spain (ESP) and Portugal (PRT), and this is natural

because of the low GDPpc level in 1960 in both countries. Germany (red line) is close to the bottom

together with the Kingdom of the Netherlands (NLD) and the United Kingdom. Figure

3 displays similar curves but for the period between 1997 and 2018. Since 1997,

Germany (DEU) is by far the leader of the race. Cumulative GDPpc growth is 1.51

compared to the second place occupied by NLD - 1.42. It is important that the agreement

of the ECB was signed in 1997. Instructively, Italy and France are much close

to the bottom of the list. The UK is in the middle. As we mentioned in previous

posts, the higher is the real GDPpc growth rate the lower is dGDP relative to

CPI. Germany, Netherlands, France, and Italy are the best examples.

In Figure 4, I am

trying to understand the influence of EU subventions on East European

countries. The overall real GDP growth since 1997 is spectacular in Poland,

Hungary, and Bulgaria. Their corresponding curves are much above Germany and The Netherlands. One might suggest that the EU financial and other assistance has a positive

impact on real economic growth in these countries. However, Serbia demonstrates

almost the same growth rate since 1997. It might be an indication that the EU

help is not so much effective.

b)

d)

Figure 1. See text for details

Figure 2.

Evolution of GDP per capita normalized to 1960 in selected EU countries between

1960 and 1996.

Figure 3. Evolution of GDP per capita normalized to 1997 in selected EU countries between 1996 and 2018.

Figure 4.

Evolution of GDP per capita normalized to 1997 in selected EU countries between

1996 and 2018.

“A United States of Europe under

capitalism is tantamount to an agreement on the partition of colonies. Under

capitalism, however, no other basis and no other principle of division are

possible except force. A multi-millionaire cannot share the “national income”

of a capitalist country with anyone otherwise than “in proportion to the

capital invested” (with a bonus thrown in, so that the biggest capital may

receive more than its share). Capitalism is private ownership of the means of

production, and anarchy in production. To advocate a “just” division of income

on such a basis is sheer Proudhonism, stupid philistinism. No division can be

effected otherwise than in “proportion to strength”, and strength changes with

the course of economic development. Following 1871, the rate of Germany’s accession of strength was three or four times as

rapid as that of Britain and France, and of Japan about ten times as rapid

as Russia’s. There is and there can be no other way of testing the real might

of a capitalist state than by war. War does not contradict the fundamentals of

private property —on the contrary, it is a direct and inevitable outcome of

those fundamentals. Under capitalism the smooth economic growth of individual

enterprises or individual states is impossible. Under capitalism, there are no

other means of restoring the periodically disturbed equilibrium than crises in

industry and wars in politics.” Lenin V.I., 1915, “On the Slogan for a United

States of Europe”.

No comments:

Post a Comment