Девальвация валюты — это

процесс, отличный от инфляции цен, которая обусловлена только

внутриэкономическими факторами. "Вертолетные" деньги, вливаемые в

экономику, эквивалентны девальвации: человек получает больше единиц платежа без

соответствующего изменения количества товаров и услуг для покупки. Федеральная

резервная система США вводила в экономику деньги через различные механизмы с

2009 года, как показано на рисунке 1 (заимствовано с веб-сайта Federal Reserve). Можно

видеть, что всплеск 2020 года был чрезвычайно большим как взрыв. Мы уже

обсудили этот эффект и описали его влияние на текущие оценки инфляции в этом

блоге. Мы ожидаем ценовой дефляции во второй половине 2022 года.

Модель, связывающая скорость

изменения реального ВВП на душу населения, rGDPpc, и уровня безработицы, u, критически зависит от точности оценок обоих параметров.

Реакция на меры Федеральной резервной системы в период с 2009 по 2020 год

должна быть аналогична реакции на рост активов в 2020 и 2021 годах —

девальвация, проявляющаяся в виде ценовой инфляции. Разницу между реальным

экономическим поведением и денежными спекуляциями следует рассматривать в

долгосрочной эволюции экономической связи между rGDPpc и u.

Как видно из рис. 1, фактор девальвации до 2009 г. отсутствовал. Таким образом,

введение столь значимого фактора в основные экономические показатели (влияние

совокупного количества денег на номинальный ВВП) должно было проявляться в виде

структурного разрыва в долговременной функциональной связи rGDPpc и u. Такой

разрыв мы нашли в 2010 г. – коэффициент линейной регрессии составлял -0,465 до

2010 г. и только -0,26 после. Эти оценки были сделаны методами, основанными на

среднеквадратичных ошибках. Константа регрессии также изменилась с 0,907 до

-0,25. Изменение этих коэффициентов позволило сопоставить данные за период с

2010 по 2019 год, как показано на рисунке 2. Коэффициенты регрессии,

рассчитанные для периода между 1979 г. (год значительного пересмотра определения

ВВП и безработицы) и 2009 г. (показаны красным), не могут предсказать уровень

безработицы на основе реального ВВП на душу населения. Тем не менее, даже

обновленная модель выходит из строя в 2020 году, о чем говорится в этом посте.

Учитывая (вертолетные) деньги,

влитые в экономику США, мы предполагаем, что экономически обоснованные оценки

реального ВВП на душу населения были искажены девальвацией, добавленной к

фактической инфляции цен. Эта гипотеза предполагает, что реальные значения ВВП

были занижены, поскольку уровень инфляции в США был завышен. При компенсации на

девальвацию коэффициенты регрессии, полученные за период с 1979 по 2009 год,

должны быть действительными, и мы можем оценить rGDPpc из u, используя

долгосрочную связь. Чтобы спрогнозировать правильный уровень инфляции и,

следовательно, реальный ВВП, мы ввели линейную функцию инфляции, изменяющуюся с

3,8% в 2010 г. до 2,8% в 2019 г. - впрыск денег не был постоянным во времени.

На рис. 3 сравниваются опубликованные и скорректированные оценки rGDPpc, а на рис.

4 представлено соответствие модели между 2010 и 2019 годами с исходными

коэффициентами регрессии. На рисунке 5 сравниваются скорости изменения rGDPpc для

скорректированных и опубликованных значений. Фактические темпы инфляции цен

были ниже опубликованных на разницу между скорректированными и опубликованными

значениями rGDPpc,

как показано на рисунке 6.

Поправка инфляции цен на девальвацию,

вызванную действиями ФРС, предполагает,

что реальный ВВП на душу населения рос в среднем на 3,2% в год в период с 2010

по 2019 год вместо опубликованного значения (в среднем) 1,5% в год за тот же

период. Это результат денежной поддержки Федеральной резервной системы. Эта

разница в скорости изменения в 1,7% соответствует общей сумме активов ФРС: ВВП примерно 20 трлн в год, умноженный на 0,017 =

0,34 трлн в год, или 3,4 трлн всего в период с 2010 по 2019 год. Это означает, что все деньги, влитые ФРС в экономику, в нее попали и вызвали общее повышение цен ровно на сумму повышения активов ФРС. Таким образом

связь rGDPpc-u в период между 1979 и 2009 годами все еще работает при очистке данных

по инфляции. На рис. 4 показана измеренная кривая уровня безработицы на основе

этой связи. Для прогнозируемой кривой реальный ВВП на душу населения должен

упасть на 8,1% в 2020 г. и увеличиться на 7,5% в 2021 г. На рис. 4 представлена

оценка на 2021 г.: 67200 долл. США.

Рисунок 1. Активы Федеральной резервной системы

Рис. 2. После 2010 г. связь между rGDPpc и u с обновленными

коэффициентами регрессии (черный) и с коэффициентами регрессии, полученными за

период с 1979 по 2009 г. (красный). До 2010 г. исходный временной ряд

представлен черными точками.

Рисунок 3.

Опубликованный (красный) и скорректированный (черный) реальный ВВП на душу

населения в период с 2010 по 2020 год. Модельная оценка на 2021 год составляет

67200 долларов США.

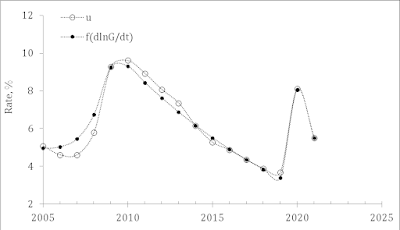

Рисунок 4. Соответствие между измеренным и прогнозируемым

уровнем безработицы для скорректированного rGDPpc.

Рисунок 5. Скорость изменения rGDPpc для

опубликованных и скорректированных оценок.

Рисунок 6. Разница между опубликованным и

скорректированным уровнем инфляции, полученная из рисунка 5.